Clinical Pearls for Treating Uveitis

By the time a patient arrives at a uveitis clinic, he or she is usually very frustrated. The patient has seen multiple doctors, and not just ophthalmologists. He or she has been on a variety of corticosteroid, topical, oral or injectable medications and may have had several surgeries. The inflammation often comes back when the medications are tapered, and the patient still doesn’t have a “diagnosis.”

The key to uveitis treatment is simple: A good workup with appropriate lab work, enough of the right medication used long enough, knowing when it’s time to move on to something else, knowing when to refer and not operating unless absolutely necessary.

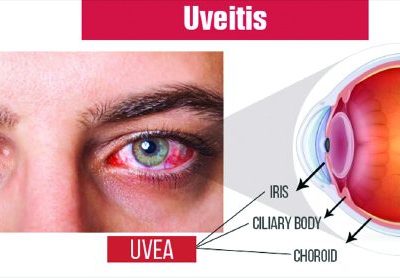

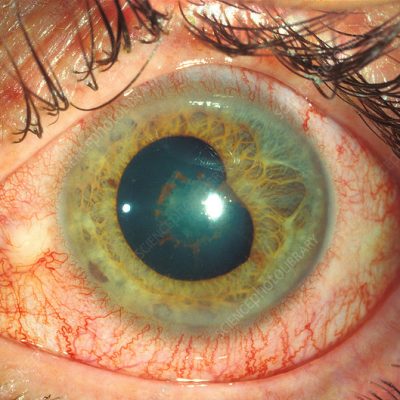

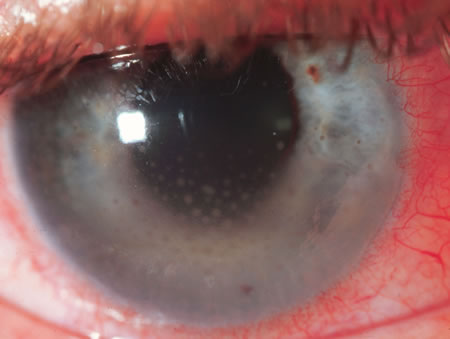

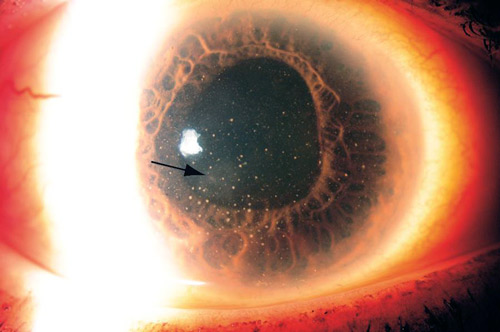

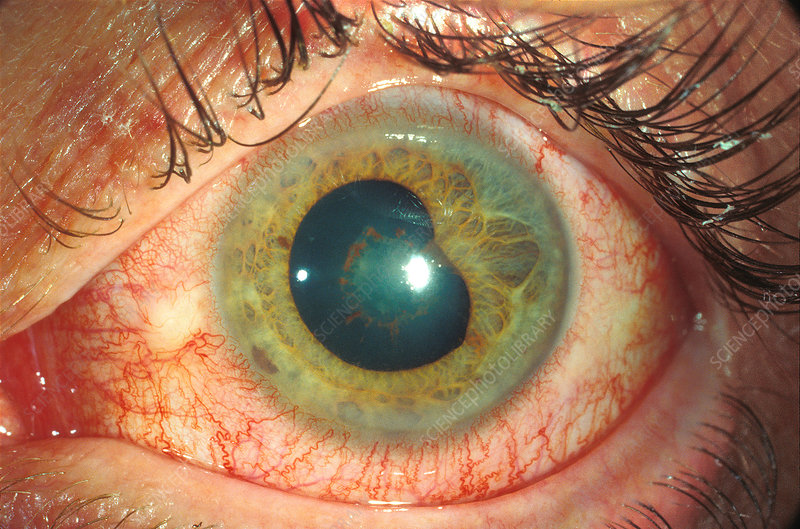

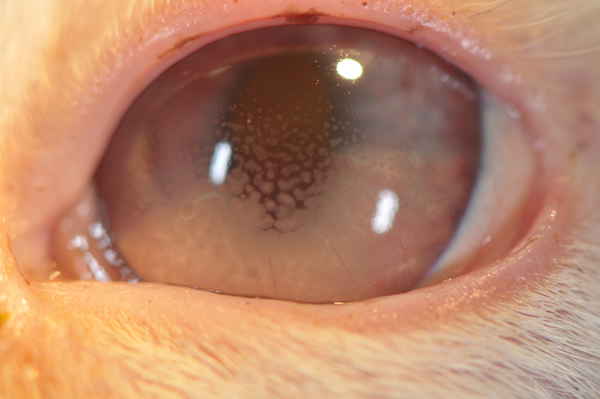

1. Anatomical location of the inflammation. Determining the location of the inflammation in the eye is critical in establishing the workup, the possible associated systemic diseases and the treatment. Pain, redness and photophobia typically indicate inflammation in the anterior segment, such as an anterior uveitis, or anterior inflammation accompanied by deeper inflammation, as in panuveitis. Floaters or visual disturbances in the absence of pain, redness and photophobia often indicate inflammation in the vitreous, choroid or retina.

2. Patient’s current treatments and medications. Find out all pertinent information, including dose, concentration, length of therapy and route of delivery. If the patient’s inflammation recurs when the drops or systemic medications are tapered down or discontinued, then the therapy was insufficient or the inflammation is chronic and requires continuous treatment. Topical corticosteroids are often initially dosed in too low a concentration or quantity and tapered too quickly. Drops are not appropriate treatment for intermediate, posterior or panuveitis because the concentration in the vitreous will be insufficient for effective treatment. Once the inflammation involves the posterior segment, either regional (injections) or systemic medications are required.

3. A targeted review of systems. Consider the anatomical location of the inflammation and ask questions accordingly. An anterior uveitis raises suspicions for positive HLA-B27-associated diseases (low back pain that is worse in the morning, heel pain, inflammatory bowel diseases, psoriatic arthritis), herpetic diseases (oral or genital ulcers, history of herpes zoster) or Behçet’s (oral or genital ulcers). With intermediate uveitis, pay attention to possible neurologic findings associated with multiple sclerosis. If panuveitis is present, consider the possibility of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) and target the ROS accordingly. Always consider sarcoid and syphilis, no matter where the inflammation is. Add Lyme disease to the workup when geographically appropriate.

4.The workup. Many diagnoses can be eliminated from the differential by doing a careful history and ROS and by determining the anatomical location of the inflammation. Think horses, not zebras. The basic workup for an anterior uveitis includes an HLA-B27, RPR, FTA-Abs, CXR and Lyme Ab, depending on geographic location. The utility of obtaining an ACE is debated among uveitis specialists because of the many factors impacting the level. For intermediate uveitis, an MRI might be necessary if the patient has neurologic findings. For posterior or panuveitis, an HLA-B27 would typically not be necessary. If the uveitis appears on examination to be infectious (toxoplasmosis or toxocariasis), the appropriate antibody screen should be obtained. Obtaining a rheumatoid factor in anyone or an ANA in an adult is usually unnecessary. The exception might be an ANA in a child with anterior uveitis and concern for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid arthritis and lupus are typically associated with scleritis, not uveitis. Lupus can be associated with an occlusive vasculopathy.

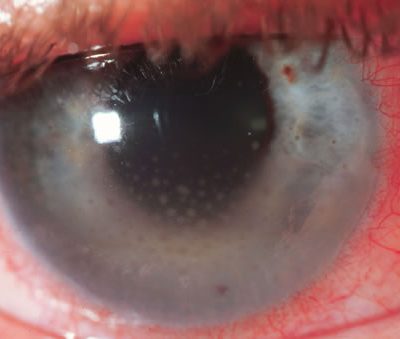

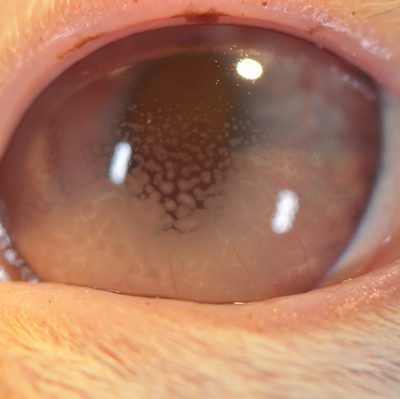

5. Corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy. For anterior uveitis, higher-potency drops, specifically prednisolone acetate 1%, should be used initially. Lower-potency topical corticosteroids should be avoided initially because of the limited concentrations achieved in the aqueous. Start with one drop every one to two hours and do not taper until a two-step improvement in the grade of inflammation has been achieved. If the inflammation has not responded within a reasonable period of time (i.e., one month), drops are inadequate treatment and therapy should be reevaluated. The median duration of an HLA-B27 attack of anterior uveitis is six weeks, so the drops should be extended for at least that length of time or inflammation may recur after they are discontinued. Local corticosteroid injections, subtenons or intravitreal, are useful for episodic intermediate uveitis associated with decreased vision or with CME. A short-term course of oral prednisone is sometimes needed, in addition to drops or injections for acute flares of uveitis. Chronic posterior or panuveitis requires longer oral prednisone therapy at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day (60 mg), followed by a slower taper to lower doses. Since the inflammation must be controlled, the temptation to reduce topical corticosteroids should be avoided. Elevated pressure should be treated with pressure-lowering drops, reserving prostaglandin analogs for last because of their association with inflammation. Rimexalone, a lower potency topical corticosteroid than prednisolone acetate 1%, is often as effective in the short-term and may help decrease the steroid-induced IOP response.

6. New approaches in immunotherapy involve more cellular-specific targeting, such as T-cells. Efficacy of the anti-TNF alpha agents has already been established in the treatment of uveitis. Local delivery systems, such as intravitreal injections of triamcinolone and sustained-release intravitreal implants, are available; intravitreal injections of nanoparticles and local delivery of immunosuppressive agents are under investigation.